SHIFTED #11: On Cyborg and Monsters, Hybrid Ecologies and Post-Natural Species

Feathers and stones, insects, butterflies, and other organic or mechanical species with that slightly bitter chemical smell, wooden display cases or glass globes, and cabinets of curiosities have always fascinated me, and even more so when they're bizarre, a mixture of unconventional things where enchantment mingles with discomfort. What if the cabinet was no longer a relic of the past? What if it looked to the future, collecting not what was but what could be?

At Machina Fauna – Exploring Post-Natural Wild, the latest exhibition I curated at Galerie Data in Paris (open from February 27 to March 15, 2025), the past and future meet into a single space. This exhibition exists in a latent space—between the memory of future species that are yet to exist and the predictions of a future fed with past images. Whether it’s AI generating data from existing datasets, 3D printing transforming raw matter into new hybrid forms, or digital tools deconstructing and reassembling nature, Machina Fauna is, above all, a story of transformation, mutation, and fusion.

Here, technology is not an external force imposed upon nature. It is inside it. Merging. Mutating. Machines don’t just mimic life; they evolve alongside it, becoming part of new hybrid ecosystems. The artists in Machina Fauna bring us face to face with this entanglement. Through AI-generated creatures, 3D-printed organisms, and digital dreamscapes, they invite us to reconsider what it means to be alive—and what comes next.

From the Cyborg to the Post-Natural

In A Cyborg Manifesto (1985), Donna Haraway shattered the illusion of biological purity. She rejected the idea of a “natural” human, untouched by technology, and proposed the cyborg as a being of fluid identities—half machine, half organic, half fictional. Today, this hybridity extends far beyond the human body. It permeates forests, oceans, fungi, and insects. Life, in all its forms, is now post-natural.

But what does this mean for art? If nature and technology are no longer separate, how do artists respond? The works in Machina Fauna push this question to its limit. They present a world where nature is not static but in constant flux, where intelligence is no longer tied to species but emerges from the spaces between them.

Ziyang Wu’s The Song of the Connectors maps the invisible networks that link biological and technological life, revealing an ever-changing ecology.

“The focus of Agartha is essentially about different modes of connections,” Ziyang explains. “What are the alternative models of connection today that we can get inspired by, that we can implement in the future?”

His work, drawn from media archaeology, field research, and science fiction, imagines a subterranean world where all living entities are linked, while humans struggle to understand and control these connections.

“The video “The Song of the Connectors #2” is based on my research of the Peruvian rattlesnakes. They can mate for six hours straight. Their twisted bodies create a temporal snake commune, echoing Timothy Morton’s idea of our dark ecology, which is a messy, entangled coexistence. It is also a metaphor while we swipe through the apps for instant likes. These snakes remind us that true bonds are forged in very slow physical struggle.”

Machines That Breed, Technology That Grows

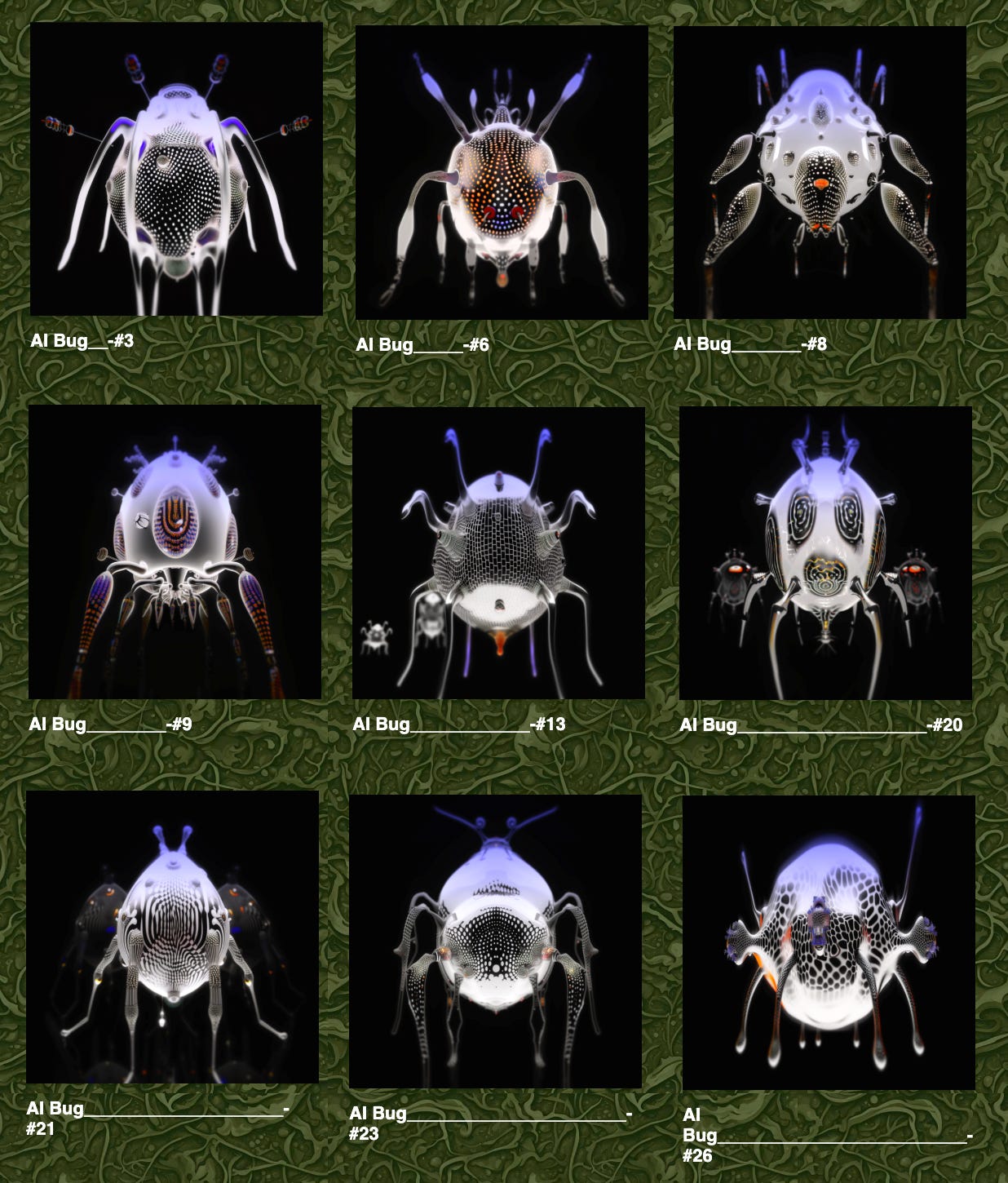

Frederik De Wilde's AI Bug_къыч'ызыp creates digital organisms that are halfway between machine error and evolutionary mutation. Frederik De Wilde, a pioneer in speculative art, first developed the AI Beetles series, which defied AI image recognition systems by generating beetle-like patterns that machine learning algorithms could not recognize. With AI Bugs, he takes this experiment a step further by asking AI to make anomalies from photos it already considers unrecognizable, effectively forcing the system to create generative anomalies. What was the result? A glimpse into a future where the definition of "natural" is redefined using artificial logic.

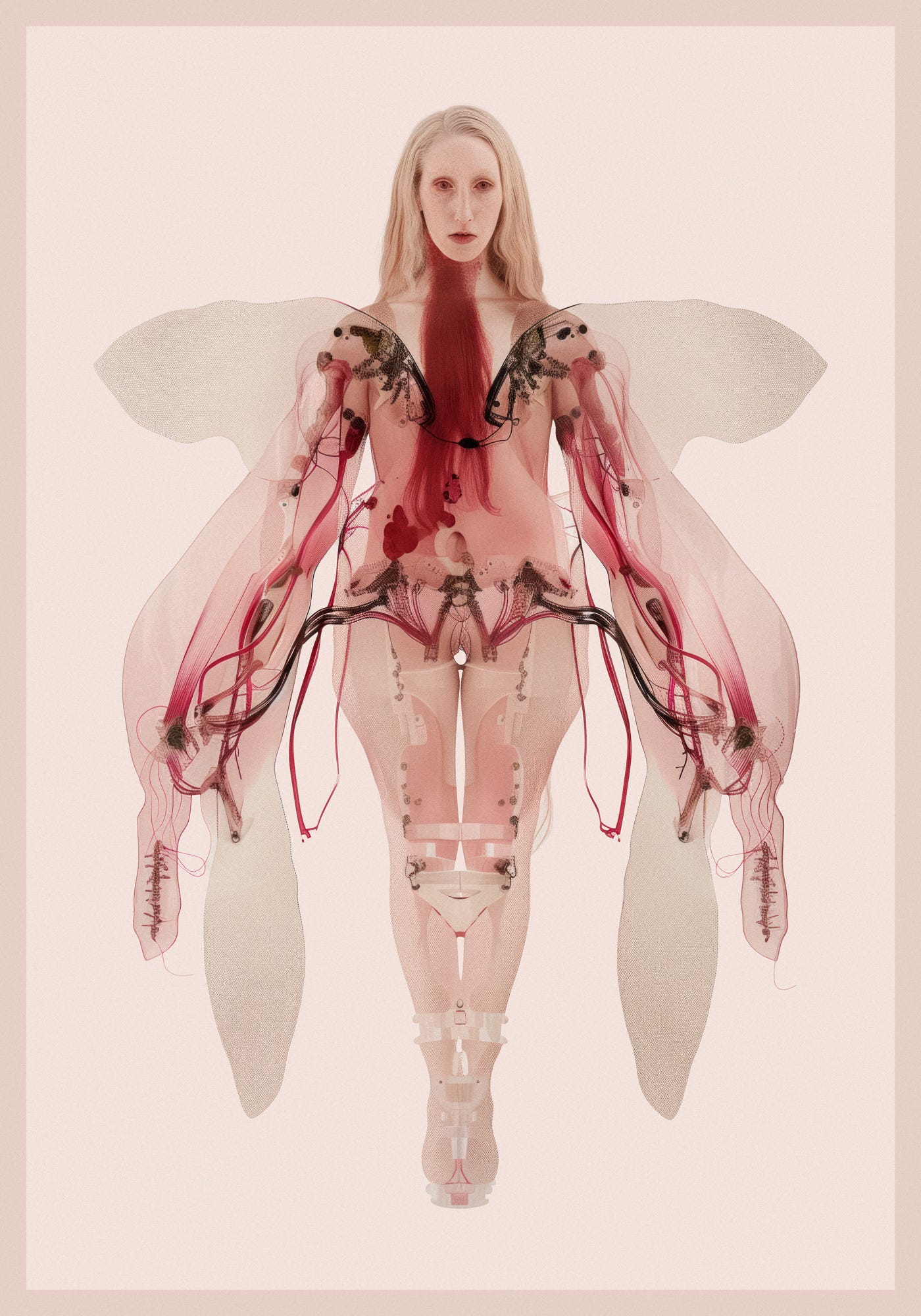

Viola Rama’s Tender Monsters presents another kind of hybridization, fusing human, plant, and animal forms in unsettling yet seductive ways. Having transitioned from traditional photography into AI art, Viola Rama critiques contemporary beauty standards and femininity, using technology to distort and redefine the body.

“I've always been interested in topics around the social commentary about female body femininity and gender stereotypes and how our society controls, especially the female bodies, because it's like a long-lasting issue in our culture.”

The idea behind Tender Monsters was to create something that looks graceful at first but then unsettles you. Reflecting on Tender Monsters, she adds:

“This series is based on my recent interest and research in the female body linked to monstrosity and grotesqueness. I use it as inspiration, like the figures of archetypal monsters in mythology and in ancient culture.” She adds: “Insects are fascinating because they represent transformation. We think of butterflies as symbols of beauty, but they also go through a violent, unsettling process to get there.”

Hypereikon's ostraciiform is morphing into a fluid, ever-changing environment that resembles a digital dreamscape. The Chilean team of María Constanza Lobos and Sebastián Rojas explores how the boundaries between the digital and the organic are becoming increasingly blurred in the posthuman future. In their practice, Hypereikon likes to challenge artificial intelligence to go beyond their existing dataset and generate images created by an “artificial imagination,” as they call it (and as Gregory Chatonski also calls AI). In ostraciiform, the AI created a speculative underwater environment that is both mezmerizing and unsettling. Also, their expertise in ethnomusicology and electronic music gives their work an extra dimension, transporting the viewer into a universe of sound.

Superpowers in the Post-Natural Wild

Finally, Manon Pretto’s Pathogène transposes these ideas into the physical world, with hybrid installations of mushrooms taking root in Galerie Data. Manon Pretto’s work embraces transformation, not as a disruption but as an inevitability. Her immersive fictional worlds explore post-natural resilience, symbiosis, and the necessity of adaptation, forming a new ecology of mutualism.

Pathogène is part of a wider body of work in which Manon Pretto is interested in biological species capable of resisting the most extreme conditions: pollution, radiation, lack of air, food, or water. These include insects, fungi and, in particular, arboreal fungi. Often considered parasites or pests, Manon Pretto turns these animals into “beings with superpowers," making them magnificient and rare.

Manon Pretto's 3D-printed sculptures, mixed with tin and synthetic materials, represent life that refuses to disappear but adapts and takes root in a foreign territory. In Galerie Data, both the cockroaches and the mushrooms invaded the exhibition space, from the vitrine to the most unusual places to display an artwork.

These hybrid forms point to new possibilities for cohabitation in a resilient rather than pure or refined world, which thrives precisely on its capacity to adapt.

The Future is Already Strange

Beyond the simple fusion of organic and synthetic, Machina Fauna is fascinating because each artist takes a different stance on the subject.

Viola Rama critiques our cultural obsession with beauty, creating monstrous hybrids that challenge perfection.

Frederik De Wilde redefines what we consider "bugs"—in a post-natural world, anomalies become new forms of life.

Ziyang Wu suggests that non-human intelligence might hold the key to escaping our own endless cycle of disconnection.

Hypereikon pushes AI beyond its learned memory, forcing it to imagine species that have never existed.

Manon Pretto proposes hybridization as a call for resilience and symbiosis, where living and non-living entities evolve together.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that insects, invertebrates, and strange biomechanical organisms dominate this exhibition. “I didn’t plan for so many insect references,” I admitted during our conversation with the artists, “but it’s fascinating to see that, independently, you all arrived at these forms.” Is it because insects exist at the boundary between organic and mechanical? Is it because their social structures resemble complex, networked intelligence? Or is it because they are among the most resilient life forms on the planet?

Are we looking at them to understand the macro through the micro? Or are we recognizing something in them—something about change, about survival, about adaptation in a world that is shifting faster than we can comprehend?

Bruno Latour, in his essay Where Am I?, describes the feeling of transformation, of becoming something else, much like Kafka’s hero in The Metamorphosis. This transformation is the need to learn to exist in a new world, a world we are the first to experience and discover. And here, of course, we’re talking about ecological change, as well as societal, technological, and political change.

Maybe the creatures of Machina Fauna are not visions of the distant future. Maybe they are already here. Maybe we are already part of this post-natural world—we just haven’t realized it yet.

Want more?

Visit the exhibition in Paris at Galerie Data until March 15, 2025 (26, boulevard Jules Ferry Paris 11)

Visit the virtual exhibition on Common.Garden

Collect the artworks on objkt.com

Blueshift News:

“Machina Fauna - Exploring Post-Natural Wild” will be presented at Galerie Data (Paris, France) from 27 February to 15 March.

“On the Edge of the Horizon”, co-curated with Tina Sauerlaender from Radiance VR, will be presented on Common Garden from 27 March to 27 April. Register here to join the virtual opening.